Welcome to the Community View section of the website. This area is dedicated to articles of interest, community information and local topics that are submitted by members of the public or guest writers. It is also the main section dedicated to the Youth Media Group Project.

On a site in Blyth Dene where Lord Delaval, in the 16th century, had once built a weir, stood an ironworks. The site is now used for receational purposes and little remains to be seen above ground of the old manufactory. It played a pivotal role, however, in the early development of the railways. This is the description from the Northumberland County History Vol 9:

"The factories known as the Bedlington Ironworks were, in part, situated within this township [of Bebside]. The undertaking originated with a lease for ninety-nine years of premises in Bebside, taken in December, 1736, by William Thomlinson, a Newcastle merchant. At this period the manufacture of pig-iron [crude iron as first obtained from a smelting furnace, in the form of oblong blocks and very brittle] in England had fallen to a very low ebb through the exhaustion of the wood required for charcoal smelting and the failure of attempts to utilise coal for this purpose. A clause in the lease empowering the lessee to cut timber in the Bebside woods seems to point to the probability of the works having been designed for smelting the ironstone deposited in the coal measures and cropping out in the banks of the adjoining river Blyth. [Armstrong's map of 1769 shows iron mines a few hundred yards downstream of the Ironworks. Even as late as 1881 some workmen of New Delaval Colliery were describing themselves as ironstone miners on the census. Christopher Bergen in the 1930s writes: Small excavations which are the result of digging for iron nodules are still visible near Kitty Brewster Farm.]

There is, however, no record to be obtained of any smelting operations having been carried on at this period. The staple trade of ironworks then consisted in the working up of scrap iron; and for that purpose forges were erected wherever the advantages afforded by cheap fuel and water power in sufficient quantities to drive small hammers could be obtained. These were both to be had at Bebside, and the works in their early stages were chiefly employed in making forgings for general purposes as well as for the Bedlington slitting mills [The slitting mill was a watermill for slitting bars of iron into rods. The rods then were passed to nailers who made the rods into nails]

Later in the century the works were carried on by the Malings of Sunderland, who worked ironstone on the north side of the river and calcined it there [reduced by exposing to a strong heat], prior to smelting it in the Bedlington blast furnace, and forging it at a forge near Bebside corn-mill on the southern bank of the stream. Their efforts were, however, attended by such poor results that they were driven to abandon the smelting operations; and the forges and works on both sides of the river were acquired, about the year 1788, by William Hawks and Thomas Longridge of Gateshead.

The new lessees extended the works and employed them in working up scrap iron into rods and hoops and other ironwork, and carried on the business into the early years of the nineteenth century, during the period when the rolling-mill was being introduced into the trade. In 1809 the works came into the hands of Messrs. Biddulph, Gordon and Company, of London, and a period of development followed under the management of Mr. Michael Longridge, who subsequently became one of the partners. Rolled iron bars, sheets and hoops, together with anchors and chain-cables for the navy, had hitherto been the chief products; but, with the dawn of the railway system, the business of the firm increased, and the fact that the first successful rolled iron rails made were produced at these works, in 1820, must have added largely to their reputation.

The substitution of malleable for cast iron in the manufacture of rails played a large part in the development of railways. So far back as 1818 Mr. Longridge had conceived the idea of connecting the works with a neighbouring colliery by means of a railway laid with malleable iron rails.

He then ascertained that rails of this description had been tried at Wylam colliery, as well as at Tindale Fell, in Cumberland, but with only partial success. The rails used at these places were formed of bars one and a half inches square and about three feet in length, having so narrow a surface as to cause injury to the wheels; while the increase in width, required to overcome this difficulty, added so largely to the weight as to render the cost prohibitive. To Mr. John Birkinshaw, the principal agent at the Bedlington works at the time, belongs the credit of having suggested the idea of making the rails in a wedge form, so that the same extent of surface, as in the case of the cast-iron rail, was provided for the wheel to travel on, and the depth of the bar was increased without adding unnecessarily to the weight. In accordance with the recommendation of Mr. John Buddle, the well known colliery viewer, the rails were afterwards made with a swell between the points of support. They thus resembled four or five of the old 'fish-bellied' rails joined in one length. They were generally twelve or fifteen feet in length and rested on bearings three feet apart. "John Birkinshaw's 1820 patent for rolling wrought-iron rails in 15ft lengths was a vital breakthrough for the infant railway system. Wrought iron was able to withstand the moving load of a locomotive and train unlike cast iron, used for rails until then, which was brittle and fractured all too easily."

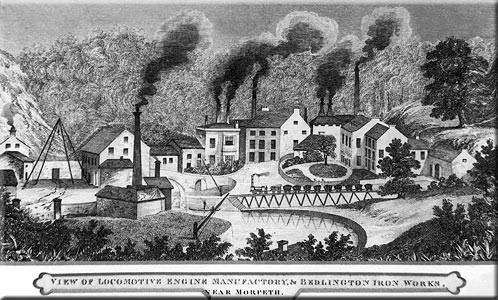

The Stockton and Darlington Railway, opened in 1825, was the first public line on which these rails were used. Its example was followed by the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, in 1830, both lines being under the superintendence of Mr. George Stephenson as engineer. [George Stephenson had a long-standing aquaintance with the owners of the ironworks and was a mentor to the engineer from Bedlington Sir Daniel Gooch as a child.] The rapid development of the railway system no doubt created an extraordinary demand for railway material, and, in consequence, the manufacture of locomotives was added to the general engineering business of the concern. In 1829 the Company purchased that portion of the Purvis and Errington estate in Cowpen township which lay nearest to the river, and erected upon part of it, in 1837, a locomotive factory, where locomotives of a high class were constructed.

.jpg)

Towards the middle of the century the business, which was then carried on under the style of Longridge and Company, or the Bedlington Iron Company, had become one of considerable importance and repute through the excellence of its manufactures. About 1840 the Longridges secured a lease of coal in the vicinity from Lord Barrington and established a winning, known as Barrington colliery, which was connected by railway with the works, and carried on partly in conjunction with them and partly as a 'sea-sale' colliery. Soon afterwards they embarked in the manufacture of pig-iron, and erected two furnaces on the north side of the river, using, as raw material, a mixture of the local coal-measure ironstone obtained from a mine at Netherton, and stone which was at that date being gathered from the debris on the shore of the Cleveland coast and used, under the name of ' Whitby stone,' by the few furnaces then at work on the north-east coast.

By about 1850 the works had reached their fullest capacity, being equipped with blast and puddling furnaces [which is a furnace that isolates the material being processed from contact with the fuel and does not use charcoal], rolling-mills, and boiler, engineering and locomotive shops, which employed a large number of workmen.

Their prosperity did not, however, continue. Keen competition in the locomotive trade and excessive cost of transit both to and from the works appear to have brought the firm into difficulties which resulted in its failure in 1853. There being then no public railway in connexion with the works, the locomotives, heavy forgings, boiler plates, and other goods had to be conveyed on rolleys drawn by horses to Newcastle, a distance of twelve miles, and there delivered, shipped, or placed on the railway to be forwarded to their destination. [Christopher Bergen in the 1930s writes: One of the great sights of the district at the time of the engine works was when a locomotive had been completed. It had to be dragged up to the steep Bebside bank of the river by a great team of horses, hired from all the farmers round about. It was generally taken from the to Brandling junction for dispatching to any great distance. Severe competition in locomotive building proved that Bedlington had been nursing the very arm that at the last would smite them low. It was easier now to move 200 tons from the north to the Midlands than it was for Bedlington Ironworks to drag their locomotives up on to the high road. It became less important that ironworks shouldbe even near to the coal mines and the advantage of river-bourne freights enjoyed by the Bedlington firm was made to look insignificant. The ironworks near the main railways were able to effect economies in the cost of transport. They were able to bear forges like Bedlington out of the market. Around 150 locomotives were built at Bedlington.]

Prior to this date the works had been assigned to Mr. James Spence, and by him they were carried on up to 1855, when they were closed for some time. In 1861 operations were resumed by Messrs. Jasper Capper Mounsey and John Dixon, who, although they appear to have conducted affairs with energy, met with no better success and failed in 1865. The business was then transferred to a company known as the Bedlington Iron Company, Limited, and continued until 1867, when the works were finally abandoned. Barrington colliery was purchased in 1858 by the owners of Bedlington colliery, by whom it has since been worked; the connecting railway was acquired by the Blyth and Tyne Railway Company, while the property belonging to the company in Cowpen township was bought by Mr. Robert Stanley Mansel, owner of the adjoining estate of Bebside. A considerable number of cottages remain at the Bank-head [and were reported to be being used by the Bebside Colliery in 1872], but the furnaces and buildings of the works have long since fallen into decay."