Welcome to the Community View section of the website. This area is dedicated to articles of interest, community information and local topics that are submitted by members of the public or guest writers. It is also the main section dedicated to the Youth Media Group Project.

It was a calm and pleasant morning as the day dawned on 12th August 1635. Blyth was a tiny and largely insignificant hamlet of a few fishermen's cottages and salt pans at the mouth of a yet undeveloped river and harbour. England was a country at relative peace with the rest of the world. By the end of the day though, Blyth would be under fire from the might of a Dutch warship. Troops would be running amok in the neighbouring countryside leaving the inhabitants in a state of terror.

The Dutch were the major military might in the area during the 17th century. in 1568 the Low Countries were part of the Spanish Empire, but rebelled against foreign rule in this year at the start of what became known as the Eighty Years War. England was also at war with Spain. It allowed the Dutch to gain control over the important port of Antwerp. They traded with countries in the East and exploited their own natural resources. There was also a huge influx of Protestant, skilled migrant workers all leading to an economic "miracle" in what was to be known as the "Dutch Golden Age".

Dutch fishing boats, known as busses, sailed the coast of Britain and the Low Countries. They were particularly active at that time of year as it was the herring season. Wallace in his "History of Blyth" (1869) explains:

"The Dutch were carrying themselves at this time with great insolence in conducting the herring fishery on our coast. They sent their ships-of-war with their fishing smacks or busses, and by the fire of their guns drove the English and Scots from their fishing grounds on their own coast. For a time the Dutch had paid a certain sum yearly to king James, for the privilege of taking herrings off the coast, but they had now not only ceased to make these payments..."

The Spanish still held Dunkirk and it was from here that privateers operated. A privateer was a private person or ship that engaged in maritime warfare under a commission of war. The commission, also known as a letter of marque, empowered the person to carry on all forms of hostility permissible at sea by the usages of war, including attacking foreign vessels during wartime and taking them as prizes. It was basically licensed piracy. The Spanish privateers were making prey of the Dutch fishing vessels.

It was the sails of a Spanish privateer emerging over the horizon and heading for Blyth that had the fishermen out in their cobles on that calm morning turn and row in all haste for the port. The privateer after some deliberation skillfully entered the harbour and docked on the North side of the river, the flag of Spain flew from the mast and three canons pointed menacingly from the deck towards the inhabitants of Blyth. The "Blyth News and Ashington Post's, Story of Blyth" (1957) states:

"The villagers had seen enough. A youth was sent running to Newsham to tell the squire, Robert Cramlington, of the sensation."

|

| Dutch Buss Fishing Vessel |

|

| Typical Privateer |

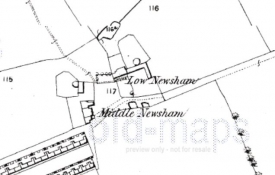

Robert Cramlington was of lesser gentry status who resided at Newsham Mansion which was on the site of the soon to be demolished North Farm on South Newsham Road. He was the landholder for all of the Newsham and Blyth Nook area. It is from the testimony of Robert Cramlington and two of his principal tenants, James Sutton, and George Fultherp, before the Justice of the Peace, Lord Delaval, from nearby Seaton Delaval Hall, that we learn so much of the incident.

Cramlington with his two aides took a small fishing boat and crossed to the privateer. He was taken to the Captain who showed him their letters of marque from the king of Spain. He explained they had come into this neutral harbour to escape and seek refuge from a Dutch man-of-war ship that was pursuing them. Their mission had been to destroy as many of the Dutch fishing fleet as possible. In this they were successful having burnt and sunk eighty vessels. The expectation was that the Dutch would not attack them in the port of a sovereign and neutral country.

How wrong they could be. Even as they were talking the sound of canon firing from the approaching Dutch ship could be heard. The Captain, probably to the astonishment of Cramlington, brought ten Dutch prisoners, captured from fishing vessels, from the hold of his ship. "Perhaps if we set them free", said the Captain, "the warship will leave and we can escape."

It seems Cramlington was also eager to escape the canon fire, which was getting ever closer. He rowed back to the hamlet of Blyth. The canon balls never did quite reach their target or the cottages of Blyth, but it did not stop the inhabitants being in great fear and taking shelter. The Dutch fishermen were set free and, after being given passage across the river, ran along the links summoning the Dutch ship to come to their rescue. A rowing boat was sent from the Dutch ship. It collected the men and returned to the vessel.

Was that the end of the incident? Could the residents of Blyth breathe a sigh of relief? Heck no! That was only the beginnings of their troubles.

"...The long boat was quickly manned with armed men. Thirty were counted by the anxious watchers on shore. The boat then entered the harbour to attack the Dunkirk privateer. But a volley of musket shots from the Dunkirkers sent the attackers hastily back to the shelter of the warship only to return in greater force. This time fifty men armed with muskets, halberds and swords were landed on the beach at the mouth of the river. They formed up in three ranks and marched up to Blyth Nook, whose terror-stricken inhabitants cowered out of sight in cottages.

"They began to fire on the privateer, which was laid at the north side of the harbour; but finding that the firing of small arms was producing little effect, they took possession of some Blyth fishing boats laying at hand, and in these proceeded to cross the river. The Dunkirkers perceiving this deserted their ship, and fled along the links. The Dutch seized the ship; but not content with this achievement, about thirty of them were sent after their flying enemies. After pursuing them for two miles, sounding a trumpet and alarming all the country side, they overtook and robbed divers of them. Ten of the privateer's men ran forward till they obtained shelter in Bedlington; a part of their pursuers still followed, but Mr. Carnaby [High Sheriff of Northumberland] was able to muster a force sufficient to apprehend and put them in prison. In the mean time the Dutch ship went to sea, taking with them the captured privateer. They continued at anchor awaiting the return of the men who had pursued the fugitives; but after learning what had befallen them at Bedlington, the captain wrote a letter to Mr. Carnaby demanding the restoration of the men." (Wallace)

Carnaby corresponded with the Bishop of Durham, who held the lands of Bedlington and its hinterland as a franchise, and sought his advice. It is also from this correspondence of the 16th August that we learn something of the incident. Carnaby had promised the Captain a reply by the evening of the 17th August.

He urged the Bishop to act in some haste as it was known there were ninety armed men on board the Dutch war ship. The whole district was in fear that the Dutch would try to take the prisoners back by force.

And that is the end of the story. It wasn't recorded what action was taken. Maybe Hollywood could provide the dramatic end in a new Johnny Depp film?

The English had supported the Dutch in their rebellion against Spanish rule, but there was a growing resentment of the rapidly expanding Dutch trade and influence. By 1652 the two countries were at war.